I learned storytelling from many different sources. There was the influence of my Irish heritage, which I received through my father’s mother. There was my father himself, a seasoned raconteur and humorist. There’s the whole Southern storytelling tradition I was steeped in growing up.

One of my chief early influences was my grandfather, Ivan Morgan Hunter. He and my grandmother lived in a small, tumbledown house on the banks of the Cherry River in Richwood, West Virginia. Richwood was built on typical West Virginia “bottom land,” where flowing water flattens out the topography between mountains and creates a flat space on which to build. In its heyday, when a lumber mill, a tannery and a paper mill were in operation in the city, Richwood styled itself as “the hard wood capital of America.” Except for the lumber mill, these industries had moved out by the late 1950s and early 1960s when I traveled there with my parents.

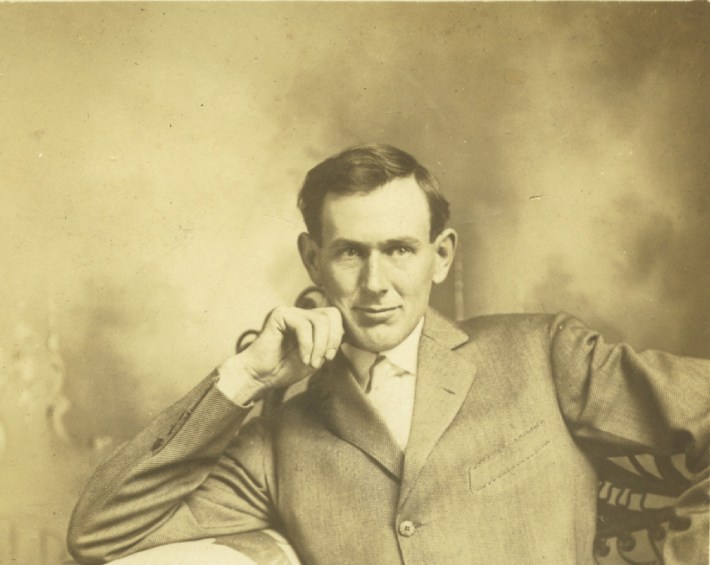

Ivan Morgan Hunter as a young man

Ivan Morgan Hunter as a young man

My grandparents’ house was actually built out over the riverbank, and was so close to the river that when you looked out of the windows on the river side, you saw the water directly below. The Cherry was a classic West Virginia river: very shallow–you wouldn’t get your knees wet wading in it–and rock strewn. When the river flooded, as it did occasionally, it would flow under the house and undermine the supports. One time in the 1950s, my grandfather injured his eye shoring up the underside of the house after a deluge.

There were several things that intrigued my childish mind about the house. It was a small house, only two bedrooms, a living room, a dining room and kitchen. There was a screened porch on the river side, where you could sit in a swing and watch the water flow. When we stayed there, I would sleep in the second bedroom. The street (“Riverside Drive”) just outside the window was actually above the level of the bedroom, because of the steep pitch of the hillside next to the house. I used to be lulled to sleep by the sound of cars going by “above” me on the street, and by the unceasing low hiss of the flowing river.

My grandmother, “Aunt Tet,” on the front porch of her house. She was housebound with severe arthritis, and so this was the outer boundary of her world. The unoccupied house fell in on the street side in 2010 and was removed by the city.

My grandmother, “Aunt Tet,” on the front porch of her house. She was housebound with severe arthritis, and so this was the outer boundary of her world. The unoccupied house fell in on the street side in 2010 and was removed by the city.

My grandfather, Ivan Morgan, had been quite handsome as a young man, and in his seventies and eighties, when I knew him, he was still quite imposing. He had grown up on a farm in rural Augusta County, Virginia. Family lore has it that a vacillating fiancée had called off the wedding ceremony one too many times, and in response, he headed over the mountains–tantamount to disappearing in those days. He landed in a lumber camp near Richwood run by Patrick “P.J.” Norton, whose large family included many attractive daughters, one of whom, Teresa, became his bride on October 1, 1915.

The Cherry floods Oakford Ave circa 1915. The couple in the jalopy may be my grandfather and grandmother; I’ve never been able to confirm this.

The Cherry floods Oakford Ave circa 1915. The couple in the jalopy may be my grandfather and grandmother; I’ve never been able to confirm this.

Although he had often worked outdoors, in his later years, he didn’t go out much–just to the corner store to get his cigarettes, or to the Moose Club to get the occasional shot of whiskey.

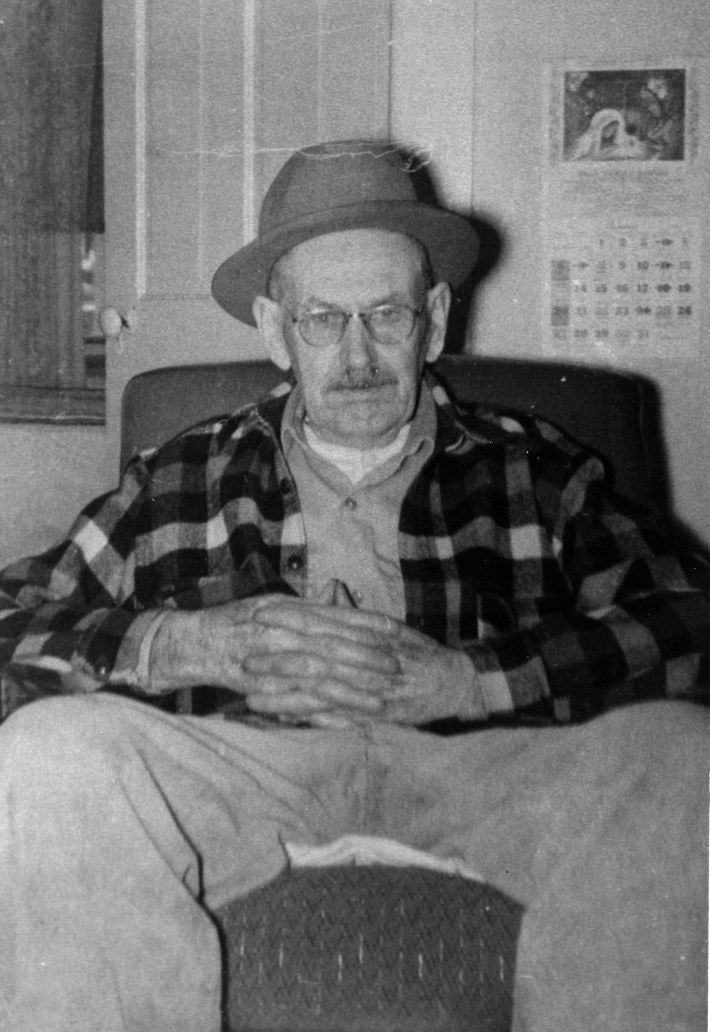

I remember him sitting in his favorite easy chair–nothing grand, by today’s standards, but perfect for him: comfortably padded, it rocked, allowing him to get out of the chair by pitching himself back and forth until he had enough “altitude” to stand.

Grandfather Hunter in his favorite chair

Grandfather Hunter in his favorite chair

My grandfather had only been in school through the eighth grade, but he never seemed uneducated. He taught himself by reading, and there were many volumes of classics packed away in the “junk room” in the back of the house. He could recite long poems from memory. When I knew him, he mainly read the Charleston Gazette, which he would pore over using a large magnifying glass he kept on a wicker side table next to his chair.

The living room was sparely furnished. There was a sofa–they found one that was rather high so my grandmother, who was crippled with arthritis, could get in and out of it easily. There was a Philco TV, bought for my grandparents by the community. When I first started going there, there was a pot-bellied stove and coal scuttle that provided heat in winter, although that was eventually replaced by a gas stove. The outer rooms got cold.

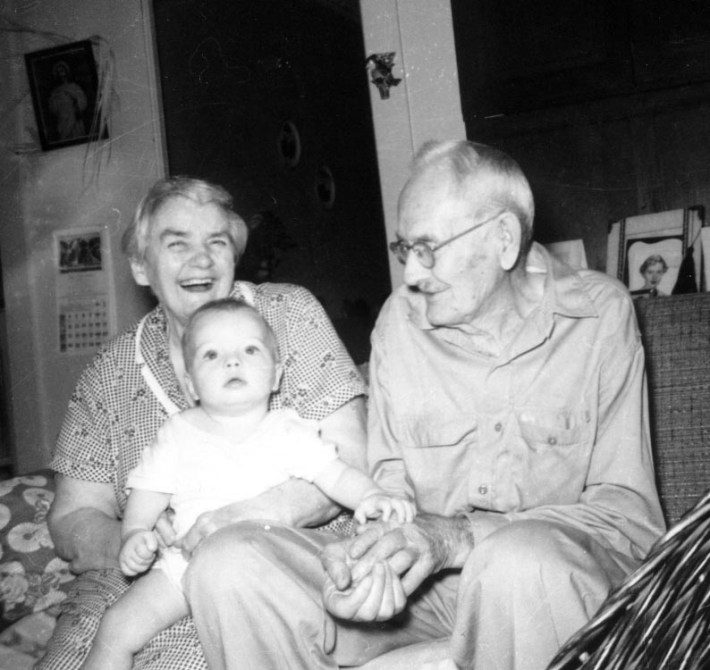

There was a big, dark wood sideboard, a remnant of more prosperous times, which displayed mostly family pictures. My grandmother had a picture of the pope, Pius XII, in one of those dual perspective images that made it appear the pope’s arm moved in blessing you if you wagged the picture from side to side. Grandma and grandpa Hunter with grandson Robert Perry Morgan. Note the palm frond from Palm Sunday draped over the picture in the upper left and the sideboard with family photos in the background.

Grandma and grandpa Hunter with grandson Robert Perry Morgan. Note the palm frond from Palm Sunday draped over the picture in the upper left and the sideboard with family photos in the background.

When we visited, my father often went off visiting his friends in town, leaving my mother and me with Ivan and “Tet,” as my grandmother was universally known (a pet name derived from her given name, Teresa). I would spend many hours sitting across from him, as he sat ensconced in his favorite chair and related experiences drawn from his working life, which included road surveying and fire spotting for the forest service. For some period, he was even a manager at the tannery. It was the fire service job–the last he held–that provided most of the material for his story telling.

In this job, he spent his days in a fire tower, high atop Manning Knob, up the mountain from Richwood. He watched for the telltale smoke in the forested expanse that indicated a fire. He spent his nights in a small cabin at the base of the tower. He walked into town once a week to get his groceries, seven miles each way. This solitary life gave him a lot of time to reflect on his experiences.

The fire tower and cabin on Manning Knob. The tower was eventually torn down, and the cabin was moved about a quarter mile away across the road.

The fire tower and cabin on Manning Knob. The tower was eventually torn down, and the cabin was moved about a quarter mile away across the road.

This reflection came out in his stories. They were not dramatic–they were often just brief vignettes or descriptions of experiences he’d had, or events or people he’d heard about. He told of things like a chestnut sapling he’d tried to rescue and a bear he’d encountered in the woods. One time he recited the entire watershed of the Cherry. He told of a man who froze to death in the woods; he told of a worker at the tannery who was operating a large overhead slicing machine that moved up and down to cut the leather into squares, who lost his forearms when he reached in to straighten the hides. He spoke with pride of a spring he had built near his fire tower.

The stories usually didn’t have any particular point, although there was often an implicit lesson. The man who froze to death, who had been found sitting against a tree, shouldn’t have gone out hunting in such cold weather. The story of the sapling was about the time he found new shoots growing out of the stump of a chestnut tree that had been killed by the blight. He thought it would help the shoots to grow if he cleared the underbrush away from them, but it actually just exposed them, and they died. Shouldn’t have done that.

Sitting there, I absorbed the arc of narrative–how to choose the story elements for maximum effect; what must be included, and in what order, so the listener will understand the story; how to add telling details to draw in the listener; how to wrap it all up in a conclusion that conveyed the import of what had just been heard.

This ability to create a compelling narrative is something I use every day in my professional life, when I write a news release or the script for a documentary. Some of the most enduring and important aspects of my own education happened early on, in that house on the banks of the Cherry.

–Joe Hunter (grandson)